Hometown Kid

You might see him strolling through the halls of Orono High School, headphones in and a grin painted across his face, and think that Guy Mohs has known nothing but joy. He walks with a swagger, and is quick to say “What’s up?” or high five a friend. This lively persona follows him on to the field. Guy has tallied 34 points and led the Orono Men’s Soccer team to a 19-1 record and a berth into the state tournament.. This gives him all the right in the world to stroll around the school like he’s on top of the world, but behind his smiling exterior, Guy has a story that is much more than the box scores and smiles.

Until November of 2013, Guy Mohs lived in Cite Soleil, Haiti. For those students unfamiliar with this Caribbean city (myself included), it is widely regarded as the most dangerous place to live in the Western Hemisphere. A shanty town that holds an estimated 400,000 people, Cite Soleil is ruled by gangs and criminals. The gangs use this town as something like a home base, holding kidnap victims and operating under heavy protection from their own. The United Nations has been fighting to regain government control of the area, but has met severe resistance. The city is impoverished beyond belief. The life expectancy is 24 years old. The situation was only exacerbated in Cite Soleil when the disastrous earthquake that struck Haiti destroyed what little order there was in the city. Amid this violence and poverty, lived Guy.

“After the earthquake,” Guy said, “I spent six months living in a tent, doing everything on my own. I searched for food, doing everything except stealing.” Despite his best efforts, Guy said sometimes he spent “two or three days without any food.” This was commonplace for Haitians after the disaster. “Living wasn’t great, but that’s how it is,” Guy said, “I didn’t get everything I needed. I got food when I could.”

As if just getting by wasn’t enough of a challenge for a teenage boy in a disaster-stricken country, he did all he could to attend school.

“To get to school was really hard for me,” he said. “We didn’t have textbooks or anything. Everything that I learned, I would have to memorize it.”

Instead of cramming the night before tests, Guy had to try and memorize every lesson taught every single day all while being unable to take notes because he simply did not have a notebook; nothing to write on.

“If I didn’t remember what I learned or what the teacher taught me, I would get beaten by the teacher,” Guy said, his voice lowered – this was not a pleasant memory for him to recount. His life in Haiti shaped who he is, but it isn’t something he would wish to go back to.

Guy is the chattiest when discussing his journey to America. He came to Minnesota first when the soccer team he was on in Haiti made the trek to play in the Schwann’s Cup, an international club soccer tournament hosted in Blaine, MN. The Mohs were his host family, along with one other boy on the team.

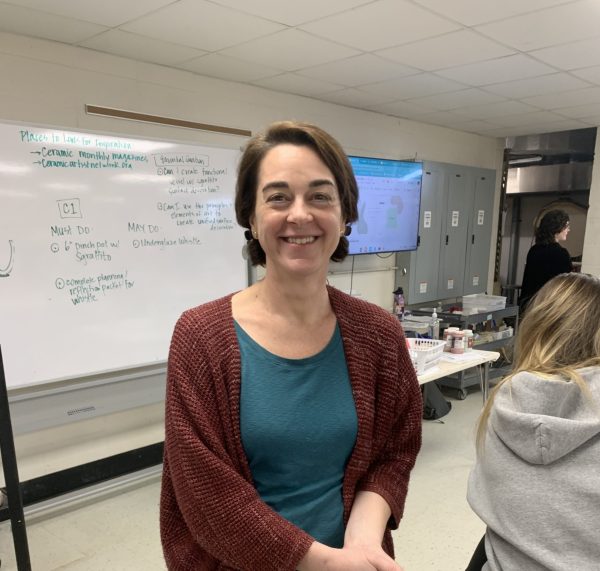

“There was something about Guy that we found very special,” Paige Mohs, the mother of the four Mohs in Orono and Guy’s adoptive mother, said. Before Guy was their host child, the Mohs family partook in a mission trip to Haiti to help relieve the devastation that had ravaged the country. Through their mission work, the opportunity arose to host soccer players from Haiti, one of which was their future adoptive son. After those two weeks had passed, “Our entire family was very sad to see him go,” she said.

After Guy had left, the Mohs thought that was the end of the road. However, when they returned to Haiti later that year on another mission trip, they saw their former host child looking worse for wear, living in the most dangerous city in the Western Hemisphere and visibly malnourished.

”I knew we had to do something,” she said, “so when I returned to Minnesota, I started looking into how he might be able to come to the US for an education.”

Her family extended a hand to Guy, and in November of 2013, Guy grabbed that hand. He travelled to live with the Mohs on an education visa. Seeing as how Guy still had a mother and father living in Haiti, the Mohs did not intend to adopt Guy as their own, but rather be a path through which he could earn an education and better his life in the U.S. This changed as Guy began to open up to his host parents about his life in Haiti. Hearing how he had struggled to even eat back in Haiti, the Mohs became convinced that the best way to help Guy would be to adopt him as their son.

“In Haiti,” Paige said, “once children, especially boys, turn 10, they are expected to fend for themselves. Even though he had a family, Guy was used to finding a place to sleep and food to eat on his own.”

Guy echoed his host parents beliefs: “It would be better for me to be adopted than to go back and forth from the US to Haiti,” he agreed, so to their biological children’s delight, the Mohs began the adoption process in March of 2014, and on August 29, 2014, Guy became the Mohs’ 5th child. By adopting Guy, the Mohs were able to keep Guy in the U.S., something that has benefited both the Mohs and their newest son.

“Since I have been in the U.S., my life has completely changed. I go to school. I have all the school supplies I need. I eat every day. I’ve gotten better at soccer. I have all the soccer materials I need.” On these last points, Guy paused. “They didn’t adopt me to come and play soccer,” he said, wanting to make sure everyone understands that he plays soccer not because his new parents expect him to, but because he truly loves the sport. His new parents did not bring him here with some set of expectations of excellence. The Mohs family adopted Guy because they love him, and they saw a bright kid living in the slums of Haiti who just needed a chance.

Though soccer wasn’t why he came to America, it still remains a major part of his life.

“I started to play soccer when I was 8 years old,” he said. “Just for fun, we played street soccer. In Haiti, soccer is the sport everyone plays. That’s all we would do.” He said that living in Haiti, he never envisioned soccer providing a path for him, but now his goal is to get a scholarship to play in college.

As much as Guy loves the sport, he said he is nothing without a team surrounding and supporting him. Moving from Haiti, he was unsure how his new team would receive him. Any fears he had were quickly alleviated.

“Everybody was friendly to me when I got to Orono,” he said. “It’s the best soccer team I could ask for, and I feel like I’m at home.”

Along with his teammates, he praised his coaches. “In Haiti, there was no one trying to help me get better, but here,” he said, “there is much better coaching. People try to help me improve.”

He has big dreams as well. In Haiti, a college education was the furthest thing from his mind. Now, it’s a real possibility. As mentioned, his goal is to get a scholarship to play college soccer, attaining both an education and playing the sport he loves. His ideal career is of course to play professional soccer. Where does he want to play? You guessed it, right here in Minnesota on Minneapolis United. Hometown kid, I guess.

Sam Sustacek: an individual that is well known throughout Orono High School. However, something that is not well known is that Sam Sustacek “really really...

Sarah Cole • Oct 27, 2015 at 1:46 pm

Outstanding story. This profile absolutely brings Guy to life with strong story-telling quotes and vivid description. Kudoes to Guy for embracing his new life, to the Mohs family for welcoming their new son, and Sam Sustacek for writing such a compelling piece.