99/1 Policy at middle school hinders incoming freshmen

Hand completing a multiple choice exam.

The 99/1 policy at the middle school has caused some controversy among students and teachers, both at the middle school and at the high school. The policy is designed so that 99 percent of a student’s grade is from summative work and the other 1 percent is from formative work.

The idea behind the policy was to emphasize learning by allowing students to make mistakes on their homework without it affecting their grade; but this, coupled with a very forgiving retake system, has instead caused the value of learning to decline.

“It’s about the reporting of student progress,” OMS principal Dr. Patricia Wroten said.

The policy gives the summative (tests, projects, etc.) category higher weight than the formative (homework, participation, etc). This allows for any issues students may have while learning new materials to not greatly affect their grades, which should reflect what they learned in the end. The biggest flaw with this is that many humans don’t do work unless they are required to.

As a result, any middle schoolers and freshmen end up not doing their homework, or “practice work”, as it’s referred to by staff at the middle school–because it isn’t something that they think will affect them. The idea behind the policy was that students would take their own initiative for learning and choose to do the work because it would help them prepare for their tests. While this is an excellent idea–and how college usually works–the system is unable to accomplish this goal.

The importance of learning has decreased because of the policy. Since students are not doing the work, or rarely doing the work, students become used to not needing to learn material–just cramming the night before, and then forgetting.

Part of the problem is the retake policy at the middle school, which further devalues learning. Many students take up the practice of failing the first test and minimally studying for the retake.

“I think [the retake policy] was one of the worst, because one, you didn’t have to do your homework, and two, you didn’t have to study for tests,” freshmen Megan Schoenzeit said,“I kinda got into the bad mindset of ‘why spend like an hour studying for the social studies quiz when I could do like ten minutes of ‘studying’ and then ace it?’”

The initiative behind the policy is noble, however it has the unfortunate flaw of being used on middle schoolers.

“We are actually training our students to be ready more for the college level with this philosophy. … A twelve year old isn’t ready for a college mindset,” eighth grade English teacher Marie Campbell said, “we have to teach them the process of being intentional about learning on the way–that you have to study.”

The prefrontal cortex in the brain is responsible for future decision making, planning, and thinking about consequences of actions. In children and adolescents, the prefrontal cortex is still developing, which means they rely on the amygdala, which is responsible for emotions, impulses, aggression, and instincts. This means that students have strong biological difficulties thinking about and realizing that homework is a crucial part of learning–and it’s not their fault. It is the responsibility of the school and the student’s parents to teach the student how to think critically and help brain development.

Reinforcing positive behaviour and punishing negative behaviour is critical for helping brain development in adolescents. Rewarding positive behaviour reinforces certain types of brain pathways–and the same applies to negative behaviour. Teaching students that their homework and studying doesn’t matter by making it virtually worthless in the gradebook is building those pathways and reinforcing undesirable behaviour.

Primary school should be about teaching students how to learn, while secondary school is preparation for college. Students in middle school are just beginning to read to learn things, rather than learning how to read. In fact, they’re learning how to read actively rather than passively.

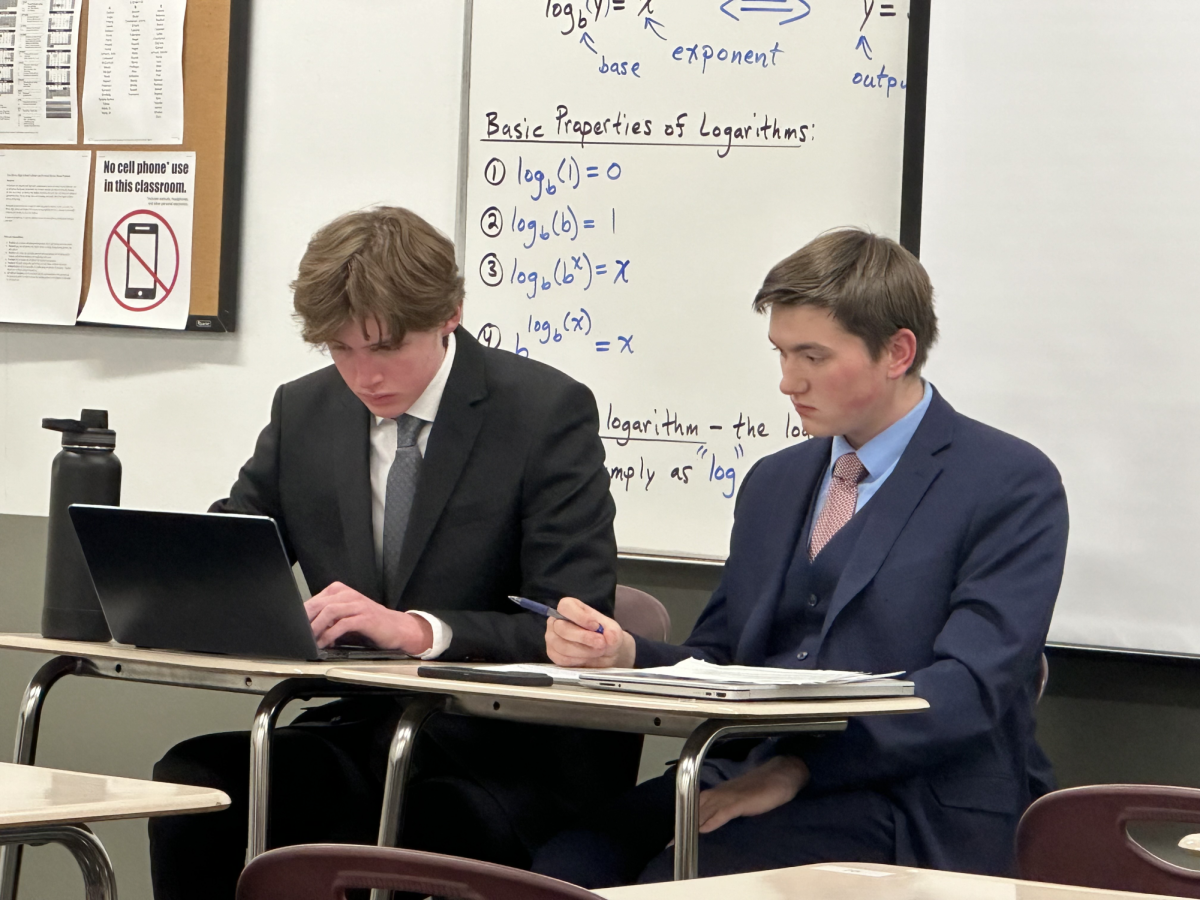

Once students hit high school they are expected to know how to learn and study on their own, however this seems to be a problem demonstrated by the freshmen and sophomores, and even some upperclassmen. Students don’t know how to handle the learning they’re expected to do on their own, and are consequently do poorly in class. Seniors still are learning skills they should have learned in middle school, such as reading a textbook or even doing proper, efficient annotations.

Incoming freshmen are unprepared and the high school policies come as a great culture shock to them. Many are forced to quickly learn how to regularly do their homework and how to study.

“[There’s a] wakeup call that homework matters, and that they can’t just blow it off,” physics teacher Renate Fiora said.

While there are some students for which this system works well for–those who don’t require many practice problems to learn something, or those who don’t need to study–it is actively hindering others.

Students are thankfully learning how to do their work once they hit high school, and many middle school teachers are helping their students by creating policies that encourage doing homework and practicing good study habits. Some have even instilled policies that prohibit students from taking unit tests without showing evidence of doing the work.

“We’re in the business to help students learn,” Campbell said.