U.S. healthcare is failing its people

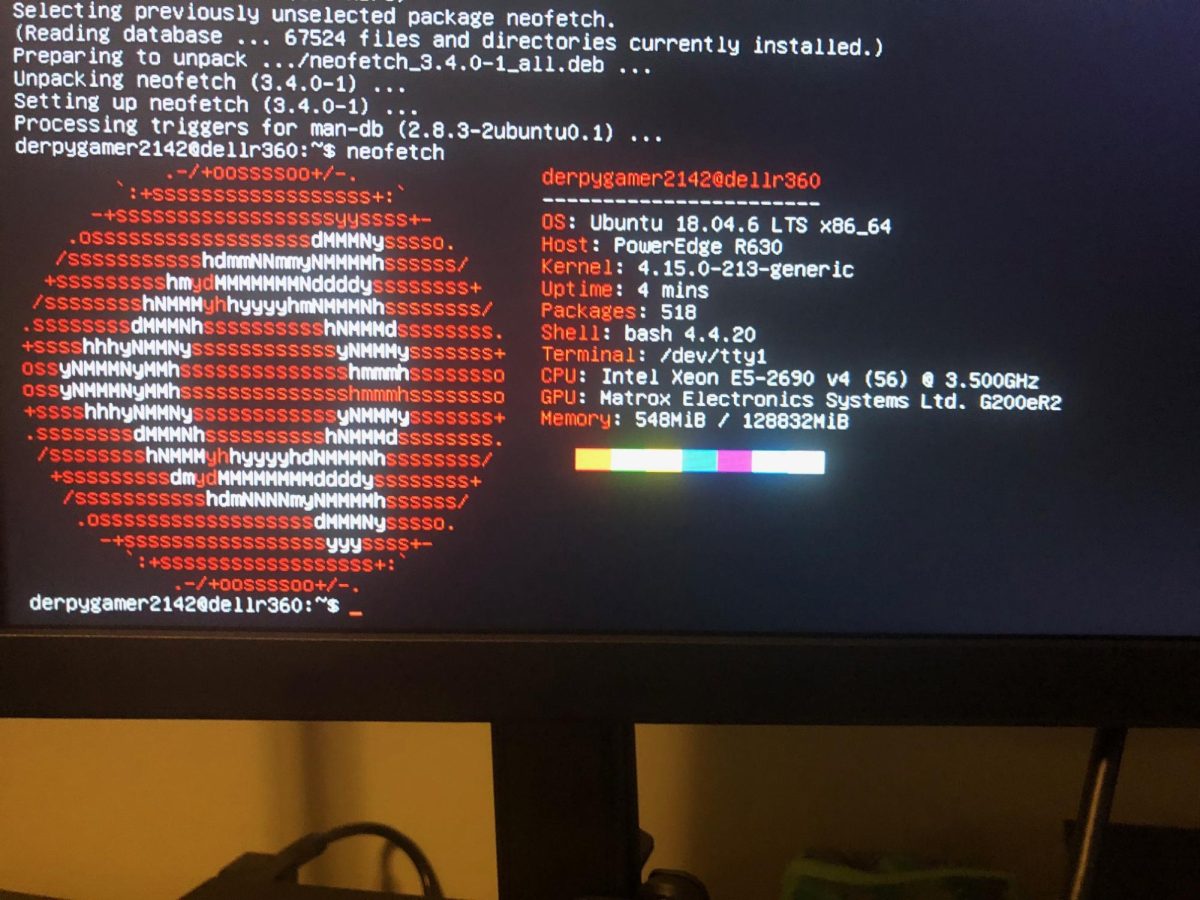

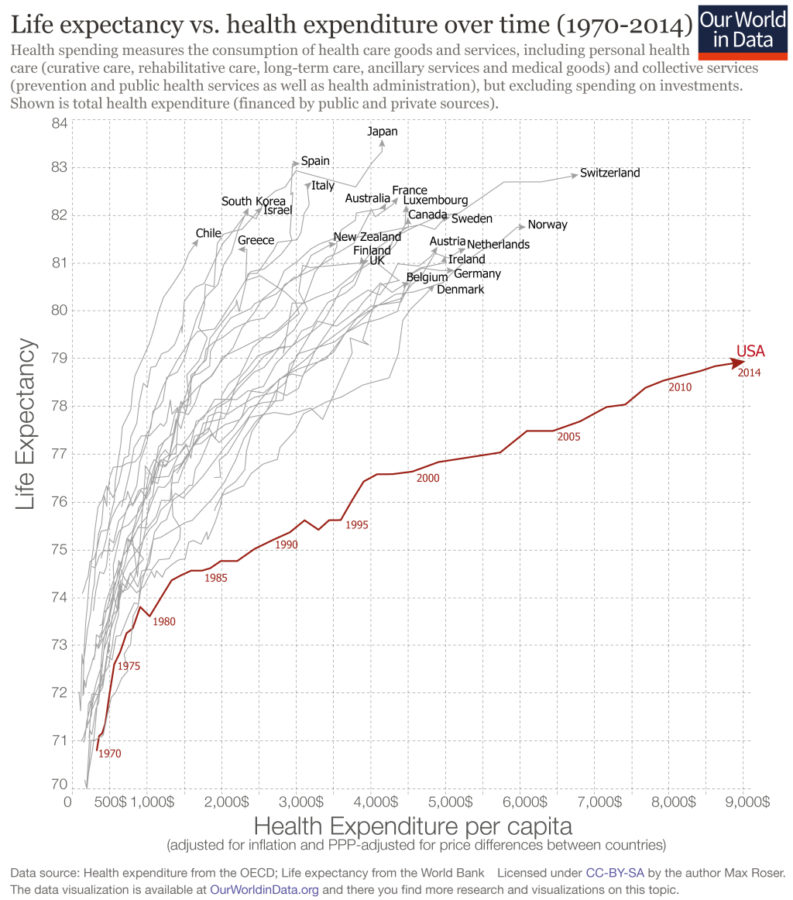

Graph demonstrating health expenditure per capita vs. average life expectancy from 1970-2014. Data source: health expenditure from the OECD, life expectancy from the World Bank. Licensed under CC-BY-SA by the author Max Roser.

How much is a human life worth, in dollars? Are some people worth more than others? These are questions that can arise when there are stark differences between the poor and the rich in a nation–and when their healthcare system is capitalized.

Americans have a strong want for an independent market and a belief in capitalism. It’s been the basis for the economy since anyone can remember, and a lot of people have shifted to thinking it’s the only way to do things. They think it can work for everything–including healthcare. Why then do capitalists from other developed countries say that healthcare cannot be capitalised?

Capitalism and healthcare should not mix. This ends up putting a price on living, saying that some people–the rich–deserve to live more than the poor. The United States is the only developed country in the world to not have universal healthcare, and is in fact the only one to not have it in the top 50 most developed countries–which includes some countries still in transition, such as Qatar, according to the WHO, the OECD, and the World Bank.

Before 1973, it was illegal to make a profit off of healthcare, and the U.S. matched the rest of the developed world. Now, U.S. per capita health spending is more than twice the average of other developed countries–in fact, it’s almost three times as much ($9024 to $3620), according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (the OECD). However, the average American lifespan–about 79 years in 2014–is much less than its counterparts, who are all above 80. Switzerland, the second highest spender at $6500, has an 83 year lifespan.

In the 1970s, the developed world sat at an average lifespan of about 74 years, but 1973 hit the US took a sharp turn for the worse. In 1973, President Richard Nixon signed into law the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973 to aid his friend Edgar Kaiser. This law now meant that hospitals, medical insurance agencies, clinics and even doctors could start to function as for-profit organizations.

Unfortunately, this law has led to a slew of issues, not just a lower lifespan than all other developed countries. Basic healthcare is insanely expensive, and the question has to be asked: Does the U.S. healthcare system value the rich, those who can afford the best insurance and the best care, more than it values the poor?

Shane Patrick Boyle died on March 18, 2017 from Type I Diabetes. For him, and other Type I diabetics, insulin is a necessity to live. He was $50 away from his $750 GoFundMe goal to buy insulin–and, unable to reach it, stretched out his remaining insulin before developing diabetic ketoacidosis, a fatal condition that results from being unable to move glucose out of the blood and into the cells.

Insulin is just one of the many medicines that is cheap and easy to produce but has seen its price rise through the roof. Its price has risen over 700 percent since 1996, according to the Washington Post. A $250 10-millilitre vial of Humalog (about a one month supply), a common brand of insulin, just costs about $27 USD in Canada.

The EpiPen is another drug that has seen its price rise. For just two pens, the cost is often over $600. This life-saving drug expires in 18 months, which makes it a frequent and expensive purchase for families, especially for families living at or below the poverty line. In Canada, two EpiPens are a third of the American price.

Why is this price difference so massive? Canada, unlike the U.S., regulates drug prices, forcing them down. The U.S. allows pharmaceutical companies to charge whatever they want, resulting in massive prices and oligopolies, which is a market monopoly, except with multiple companies in control.

“They say market forces set the prices reasonably, but there are no market forces,” said Hagop Kantarjian, chairman of the leukemia department at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center as qtd. in the Washington Post. “The drug companies are so few, they have carved out oligopolies.”

Unfortunately, in healthcare, the market doesn’t work as normal markets do, with demand and supply regulating price. Doctors pick the drug that they think will be best for their patient, ignoring, and often not knowing, price. Price is regulated under the table by pharmaceutical companies and companies that provide prescription drug benefits.

Many Americans are turning to Canada to try and buy medication they can afford. While according to the FDA it’s technically illegal, some states have allowed citizens to buy their prescriptions from Canada, and others often don’t enforce the law.

Hospital prices in the U.S. are another problem. A list owned by each hospital–called the chargemaster–dictates what certain things cost, and more often than not, the prices are massively inflated. A heart transplant that costs $302,066 for the patient in one Indianapolis hospital costs $177,297.06–almost half the price–in another, according to the CMS database for Medicare Inpatient predicted costs. Prices continue to vary across the country, sometimes with one area of a city being up to four times more expensive than another area.

Maternity leave in the U.S. is a bleak contrast to other countries. The minimum maternity leave in the U.S. is 12 weeks, unpaid. The minimum in other developed countries is three months, paid. Only Lesotho, Papua New Guinea, Swaziland and the U.S. do not offer their citizens paid leave, according to International Labour Organization.

In the U.S., the cost of giving birth is, on average, more expensive than in any other country, according to the International Federation of Health Plans. Money shouldn’t be something new mothers and fathers have to consider, but in the U.S., the average natural delivery is over $10,000, according to the International Federation of Health Plans.

The U.S. should follow the footsteps of its developed counterparts. Since the U.S. has so many resources, good doctors and excellent research, a universalized system would be a great benefit to the country. A law regulating pharmaceutical prices would be a great benefit as well. It would allow people to be able to survive and allow the country to thrive. People who are dying now to try and avoid debt for their family would be able to afford the care they needed.

The value of someone’s life cannot be capitalized, but it seems like what many politicians want. It’s important to remember they can afford whatever care they want, though. How fast would the system change if they got the short end of the stick?